Dr. Montessori often used the word, “costruire”, the translation from the Italian being “to build, create, to construct”. Before children can become Greeks (working abstractly), they must first be Egyptians (use their hands). One could write a treatise (or two!) on the myriad of ways a Montessori prepared environment provides opportunities for a child to construct, both physically, cognitively, and even as a metaphor for emotional and social growth. Specific to a manipulative material, the Geometric Cabinet can serve as an excellent model for the concept of construction.

The Geometric Cabinet is one of the more important and versatile geometry materials we have in our Montessori classroom. It is, or should be, present in every Early Childhood and Lower Elementary classroom, but it is also used (more likely borrowed) in many Upper Elementary environments as well. It is a beautiful material to display. The large wooden cabinet with six drawers brings attention to itself and adds to the impressive array of our Montessori environments.

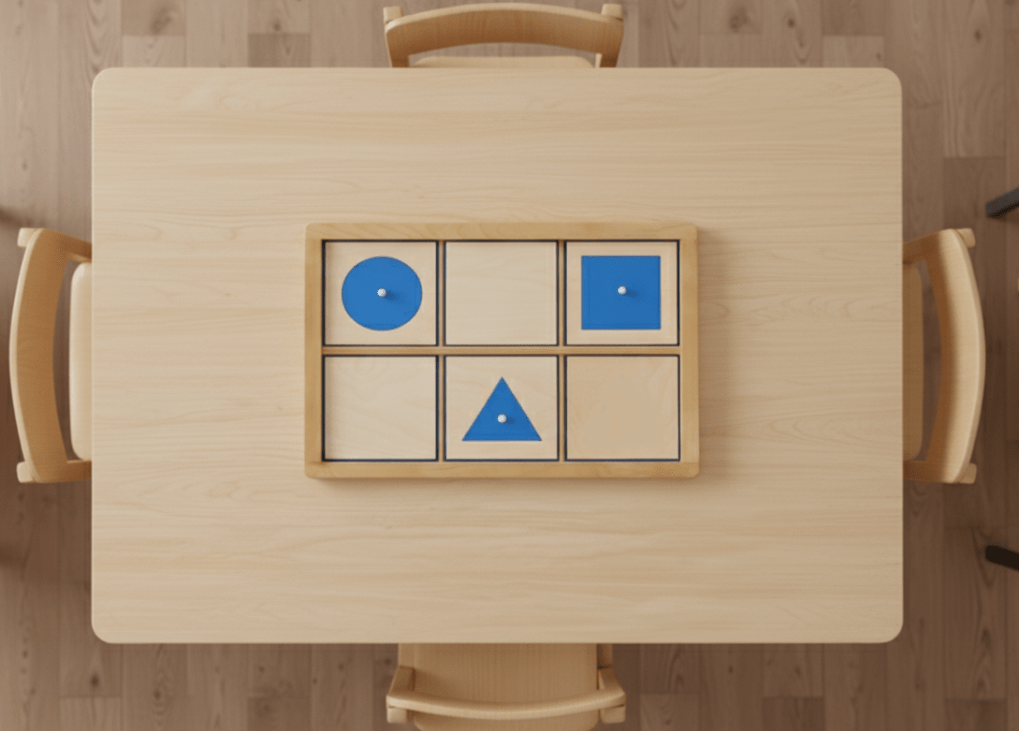

Traditionally, a “Demonstration Frame”, that sits on top of the cabinet, holds the Circle, Square, and an Equilateral Triangle. In some schools the order of the drawers differs from Early Childhood to Elementary environments. It is also important to note that there is no set of specific figures present in the cabinet. Certainly, there is always a Triangle Drawer, a Polygons drawer, a Rectangle drawer, and a Circle drawer. There is almost always a Quadrilateral drawer, but the sixth drawer can sometimes be Curved Figures, but a Miscellaneous Figures drawer is not uncommon!.

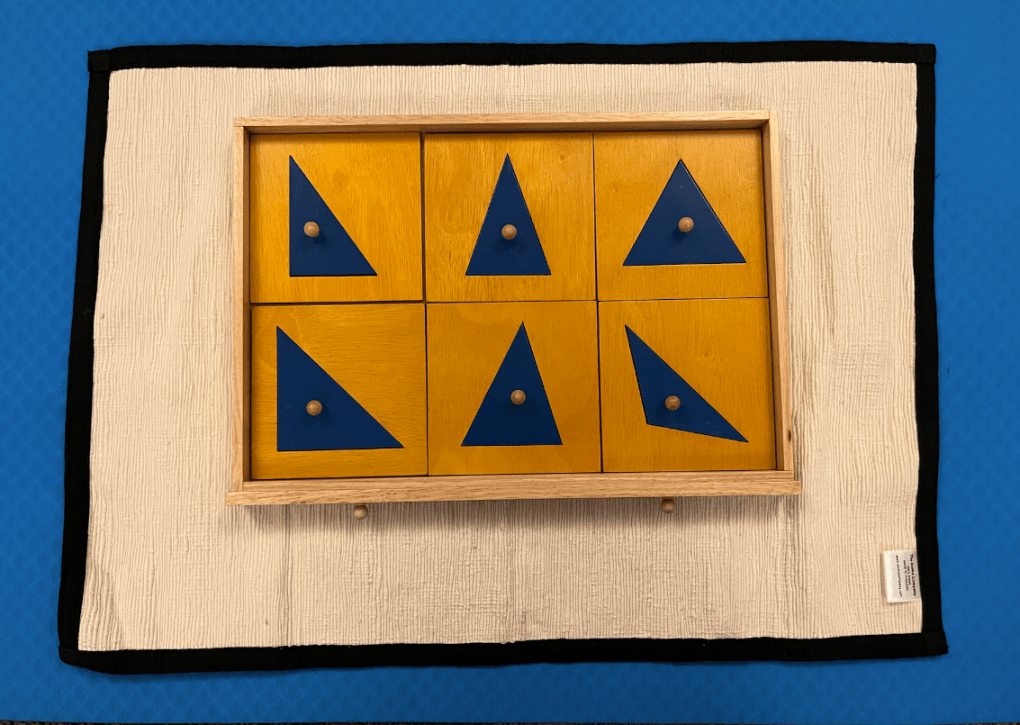

The first drawer displays triangles; acute-scalene, right scalene, obtuse-scalene, acute isosceles, right isosceles, and obtuse isosceles. The drawers present these shapes in two rows of three. How to order them? One suggestion would be the scalene, isosceles, and equilatreal across the top row to classify by sides the bottom row to show examples by angle. Right-angled in the first column, obtuse-angled in the middle column, acute-angled in the right. We put those after the right as they are both determined by their relationship to a 90 degree angle.

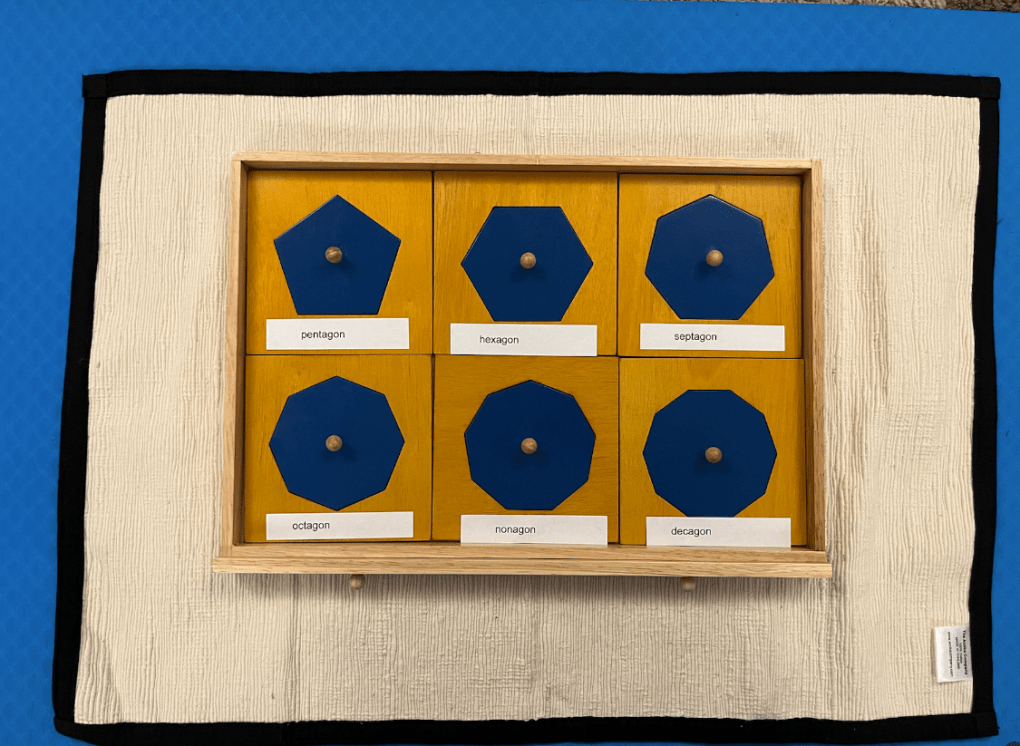

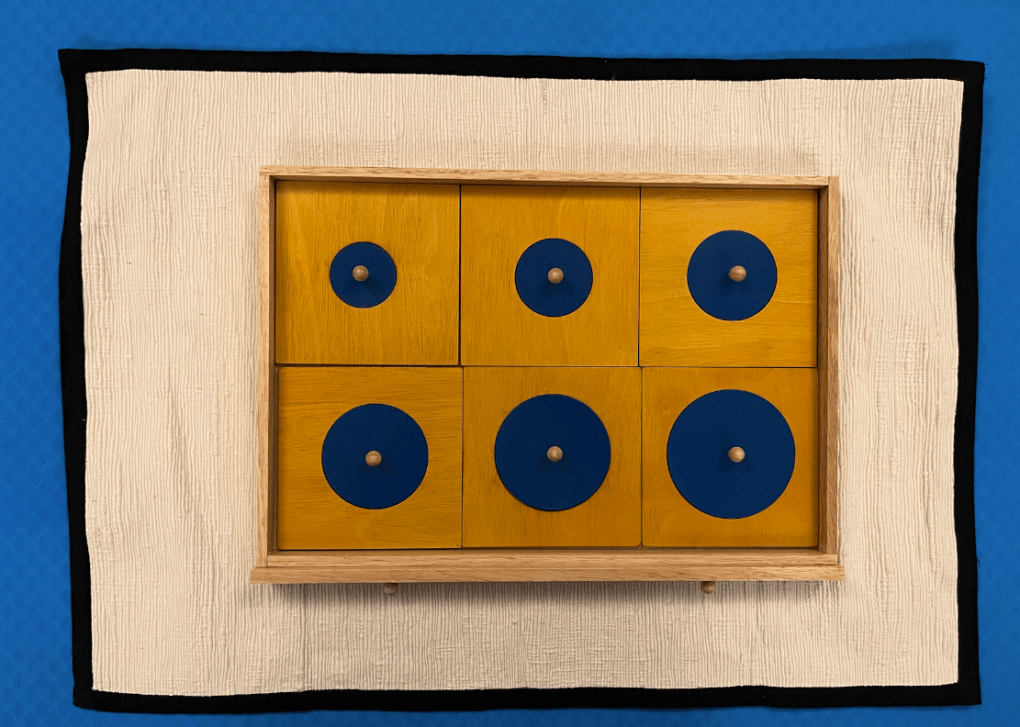

The second drawer displays quadrilaterals; trapezium (sometimes referred to as a common quadrilateral), parallelogram, trapezoid, and rhombus, The third drawer displays rectangles. There are six shapes total, five rectangles with gradually lengthening bases, and one square in the bottom right corner. The fourth drawer is a set of six regular polygons, and they are arranged by number of sides. The pentagon, hexagon, septagon make up the first row. Octagon, nonagon, and decagon round out the second row. The fifth drawer contains the circles. Again there are six, of different diameters starting in the top left (5cm) and ending in the bottom right (10cm). The 10cm circle matches the demonstration tray circle mentioned above. These drawers, with these figures, are common to every Geometric Cabinet.

A common, and desired sixth drawer contains curved figures. The oval and ellipse certainly, quatrefoils and a curviliinear triangle maybe. The curvilinear triangle can also be called a Rouleaux Triangle, named after Franz Reuleaux,a 19th-century German engineer who pioneered the study of machines for translating one type of motion into another, and who used Reuleaux triangles in his designs. As one could probably guess, the design itself predates him by centuries. Perhaps he had a better PR firm? The contents of some sixth drawers, as mentioned earlier, will use the drawer for miscellaneous figures, like the delta (kite) or a convex quadrilateral (boomerang).

The Cabinet is supported in both Early Childhood and Elementary classrooms with cards that match each figure. Typically the child starts with cards that are solid figures, then those with thick outlines, and finally a thin line outline. Labels for each figure can also be purchased or teacher-written. A companion material would ceratinly be the Constructive Triangles. It even has construct in its name, after all. It also represents a material that is presented not just in early childhood and lower elementary classrooms, but upper elementary as well.